Mateo Maximoff

English

Mateo was born in 1917 in Barcelona, Spain, where his family, after having travelled through many countries in Eastern and Western Europe, took refuge trying to escape the First World War. A few years later, in 1920, his relatives settled in France, initially as nomads, with no fixed abode, then settled in wooden huts in Pantin, near Paris, in what is still called "the zone". Their father was a Rom kalderash (coppersmith) who had left Russia with his whole family (about 200 people) at the beginning of the 20th century to flee from the Bolsheviks. His mother, came from a family of manouches from France. Before that, his ancestors had lived for five centuries as slaves in Moldavia and Wallachia, principalities of present—day Romania.

Mateo never set foot in a school. His father, a coppersmith, spoke French badly and his mother, a circus performer, was illiterate. At the age of five he already spoke several languages, but he did not know how to write because no one had taught him. His father, who could read and write a little, taught him to count (it was important for work) and then taught him to write the letters of the alphabet. That was all his teaching. The rest, he acquired on his own. Completely self—taught, he learned from everything he could get his hands on: newspapers, magazines, low—quality novels, and great classic authors. His mother died when he was eight years old and his father died a few years later. At 14, he was the oldest of five children and had to work to feed his brothers and sisters. Initially, he worked as a coppersmith, just like his father.

At the age of seventeen, he was married to an older woman, with whom he had a son, Bourtia. But the marriage went badly, they separated and Mateo distanced himself from his Roma family. In 1935, after this separation, Mateo left in search of his mother's Manouche family, who travelled by caravan through central France. For two years, he shared a nomadic life with his maternal aunts and uncles and with his cousins. He was at the same time a circus worker, a traveling salesman and, best of all, he projected movies on an itinerant basis in various villages. Cinema was his new passion and he discovered, among others, the films of Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. Later, he would collaborate first as an extra, and then as an assistant to the extras in numerous films.

At this time, when he was 21 years old, a dramatic event led him to write. In Auvergne, near Clermont—Ferrand, two Manouche families violently confronted each other over the honour of a young girl. One of these families was that of Mateo. There were numerous injuries and several deaths. Mateo, like other members of his clan, was arrested and put in prison on charges of collective murder. But Mateo had not killed anyone, he had only tried to protect his own. In prison, Mateo wrote a letter to his lawyer, a young intern named Jacques Isorni who would later become famous for his defence of Marshal Pétain. The lawyer, surprised by the young gypsy's ease with which he expressed himself in writing, asked him to tell his version of events in detail, in order to be able to support his defence. Mateo did so and in a few pages, he described the events of that tragic night. Lawyer Isorni, impressed by Mateo's personality, sensed that he had a genuine talent as a storyteller and, possibly, as a writer. He provided him with paper and pencils to write, and encouraged him to take advantage of his incarceration to write.

This was a very difficult period for the Gypsies. Few people know it, but the Gypsies were persecuted just like the Jews, as undesirables and people of an inferior race, and more than five hundred thousand perished in the Nazi camps. Fortunately, Mateo and his family escaped deportation to the death camps. They spent most of the war under house arrest in the internment camps of Gurs and Lannemezan in the Pyrenees, in terrible conditions that left him with physical and psychological scars. He would often recall in his writings his suffering and that of his people during this period. During his confinement in the camps, he wrote numerous stories, drafts of novels and poems, based on what was narrated by his great—uncle Savka. Most of these writings have unfortunately been destroyed, or simply lost.

When the war ended, he and his family, as well as hundreds of other Roms and refugees of all kinds, Spanish, Italian and others, settled in barracks, tents and caravans in the Paris belt, which is still called "the zone".

Mateo's first novel, Les Ursitory, was published in 1946 by Flammarion, thanks to the perseverance of lawyer Isorni who had befriended the young man. The novel was an immediate success upon its publication. This young gypsy who wrote in such a particular style, sharp and lively, intrigued and seduced. It did not take long for him to acquire a certain notoriety in the literary media. Newspapers, radio, and television in the 50's dedicated articles and broadcasts to him. For a long period of time, he only wrote for newspapers and magazines. In the 1950s, he returned to writing and published two new novels with Flammarion: Le prix de la liberté and Savina. He gave interviews and lectures on gypsies and participated in the creation of associations such as Les Etudes tsiganes. The world of cinema frequently called him for films featuring gypsies: Singoalla (1949), La caraque blonde (1953), Elena et les hommes (1956), Goubbiah mon amour (1956), Cartouche (1962), Les amants de Teruel (1962), Kriss romani (1963). At this time, many producers approached him to stage Les Ursitory but no project went ahead.

In 1952, Mateo married Jacqueline, a young Swiss woman with whom he began an epistolary relationship, and who fell in love with him by reading his books and letters. She had a daughter from a first marriage named Carmen. They settled together in Montreuil-sous-Bois where Mateo's Rom family lived. Jacqueline was renamed by the family as Tita, and her daughter Carmen as Savina. Sometime later, in 1953, this marriage gave birth to a girl they named Nouka.

The beginning of the 1960s marked a decisive turning point in his life.

For some time, he had been hearing about a new religious movement that reached many gypsies: the evangelical movement. Touched by grace he converted, and his faith was so strong that in a few months he became pastor and missionary of the Mission Evangelique des Tziganes in France. He consecrated his life to God and travelled the world in search of his Rom brothers and sisters, to bring them the Gospel.

His new role led him to translate the Bible into the Kaderash dialect of the Romani language, but only the New Testament and the Psalms were published.

However, his religious commitment did not put an end to his literary activity, quite the contrary. He wrote the novels: La septième fille, Condamné à survivre, La poupée de Maméliga (fantasy novels), Vinguerka, Dîtes—le avec des pleurs, Ce monde qui n'est pas le mien and Routes sans roulottes, which is an autobiography.

All his books were published in French and translated into a dozen languages. In 1986, his literary work was crowned by the award of the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres medal. In 1983, he himself founded the Prix Romanès to promote gypsy culture.

Matéo Maximoff was not only a well—known writer but also a storyteller, poet, filmmaker, photographer, reporter, militant for the cause of the Roms, and also a pastor. His exciting life was the subject of a biography written by his friend Gérard Gartner: Matéo Maximoff, carnets de route, as well as numerous articles in the journal Etudes tziganes which in 2017 dedicated a special issue of 160 pages to him. His name is cited in almost all the books that appear or have appeared concerning the Gypsies. Since 2014 a media library in Paris bears his name.

Mateo's first objective in writing all his books was, above all, to make the Gypsy culture known to the Gadjés (non—gypsies) all over the world. He had also made it his mission to preserve this essentially oral culture, leaving a written and lasting trace that would allow future generations to get to know it. He later translated some of his books into Romani, but they have never been published, basically because of technical problems with the transcription of a language that never had a script. Mateo's novels and short stories are of ethnographic interest to scientists and researchers because they are set in Romania during the time of slavery (Le prix de la liberté), in the Russia of the Tsars after the Bolshevik revolution (Vinguerka, Ce monde qui n'est pas le mien), in a Europe shaken by the Second World War (Condamné à survivre), in internment camps (La septième fille). The two autobiographical novels: Dites-le avec des pleurs and Routes sans roulottes are closer to the contemporary world. All his novels give a particular focus on these periods of European history and on the history of the Gypsies in Europe. On the other hand, all the stories that take place among the Gypsies provide a lot of information about the customs, traditions, and ancestral beliefs of this People.

Mateo Maximoff died on November 24, 1999 in Romainville. He remains today the first and most famous Gypsy writer of the 20th century. His out-of-the-ordinary personality, his prolific work and his commitment to the Roms make him an indispensable author of Gypsy literature in the world.

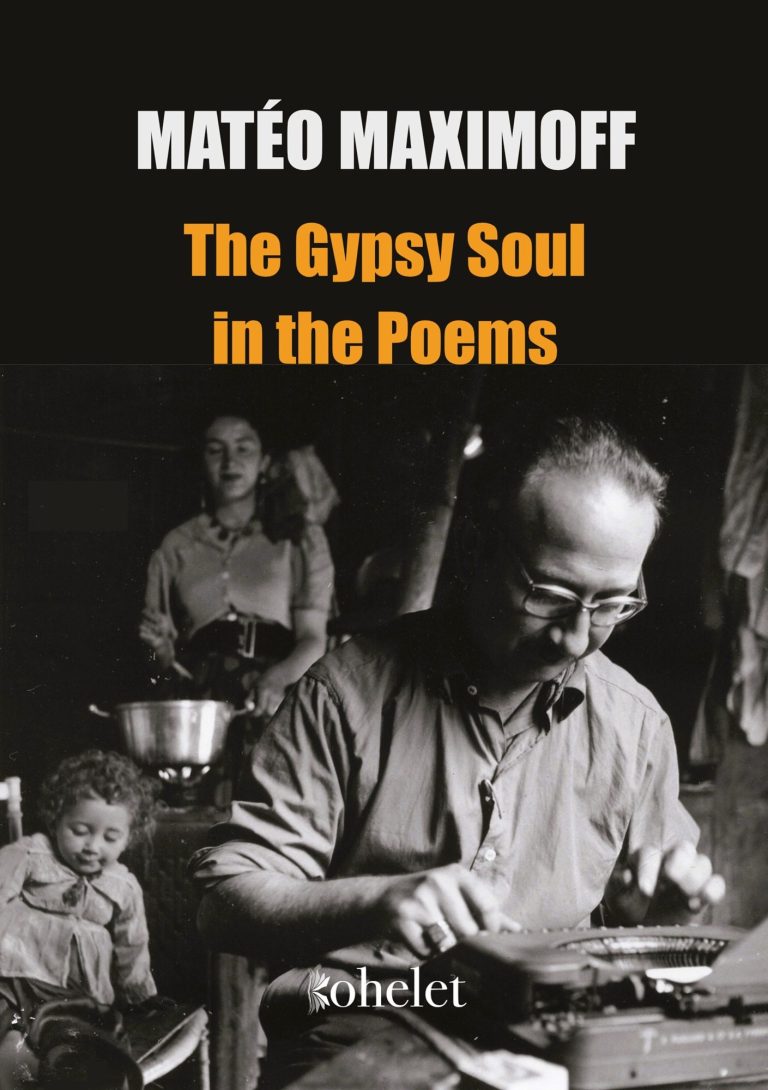

The Gypsy Soul in the Poems

Mateo Maximoff (1940-1983)

This collection offers a rare opportunity to explore the poetic legacy of Matéo Maximoff, whose poems have never been translated into English before. His work deserves recognition, and the publication of this collection is an essential step toward acknowledging Gypsy literature on an international level. Maximoff's poems, rich with vivid imagery, musicality, and profound emotional depth, transcend personal experience and become the voice of an entire people. They weave together folklore traditions with an individual authorial style, creating a unique rhythm that, we hope, will resonate with a broad audience. This collection not only broadens our understanding of Maximoff's poetry but also contributes to strengthening the presence of Gypsy literature in the global cultural space

Матео Максимофф

ISBN 978-84-129534-9-7

E-book

Завдяки зростанню інтересу до національних літератур і перекладу творів українською мовою творчість циганських авторів стала більш доступною для широкого кола читачів, хоча їх публікації досі залишаються епізодичними. У цьому контексті публікація збірки віршів Максимоффа має особливе значення. Вона не лише відкриває нові грані його творчості, а й сприяє інтеграції європейської циганської літератури в культурний простір України.

Популяризація циганської літератури — важливий крок до її визнання як невід'ємної частини світової літературної традиції.

Сподіваємося, що публікація цієї книги надихне дослідників, читачів і нових авторів на подальше вивчення та розвиток циганської поезії в Україні та за її межами.

Ілона Махотіна

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

ПОЭЗИЯ МАТЕО МАКСИМОФФА

Илона Махотина,

кандидат филологических наук,

цыгановед

«Ему также случалось писать стихи — простые и без претензии на стиль. Он просто, но искренне выражал то, что у него было на сердце: свою боль, свои страдания, реже – свою радость и надежды».

(«Dites-le avec des pleurs», 1990)

Настоящий сборник — peдкая возможность познакомиться с поэтическим наследием выдающегося цыганского литератора, чьи стихи ранее не были переведены на русский язык. Несомненное литературное мастерство ставит Максимоффа в один ряд с лучшими цыганскими поэтами мира. Есть свидетельства, что он свободно владел русским языком – вторым языком семьи своего отца, что делает его творчество еще более значимым для русскоязычного читателя. Стихи Максимоффа, полные живых образов, музыкальности и глубокой эмоциональности, не только отражение его внутреннего мира, это голос целого народа. В них сплетаются фольклорная традиция и индивидуальный авторский почерк, создавая особый ритм, который, надеемся, найдёт отклик у самого широкого круга читателей. Публикация этого сборника — дань уважения таланту автора и важный шаг к признанию цыганской литературы.

ISBN 9788412953442

Ціна волі

ISBN 979-13-990347-1-4

Мало хто знає, що циганський народ перебував у рабстві протягом п’яти століть у князівствах Молдови та Волощини. І що в горах переховувалися та вели боротьбу цигани «поза законом», поки у 1856 році, під впливом визвольних ідей у всій Європі, рабство не було скасоване.

Головний герой роману, Ісван, проходить шлях від бібліотекаря та особистого секретаря воєводи до очільника визвольного руху. На його долю випаде багато випробувань, любовних пригод, боротьби та смертей. Він буде несправедливо звинувачений та засуджений.

Але надія та віра у справедливість допоможуть йому вистояти, і здобути свободу та щастя.

Урситори — ангелы судьбы

E-book

Матео Максимофф родился в Барселоне в 1917 году, куда его семья перебралaсь из Российской Империи, проехав всю Европу. В дальнейшем oни обосновались во Франции, где Максимофф прожил всю оставшуюся жизнь.

В возрасте двадцати одного года он написал свою первую книгу

«Урситори», которую мы предлагаем вашему вниманию.

Возможно, вы впервые познакомитесь с творчеством цыганского авторa, пиcaвшего по— французски и при этом носившего русскую фамилию.

Вот как он сам говорил o происхождении своей фамилии:

«Мой прадед был ростом 2,10 метра и весил 180 килограммов. Когда он пошёл регистрироваться, его спросили, какую фамилию он хочет взять... И он ответил: "Самую большую — Максимофф". И с тех пор эту фамилию носит вся моя семья».

Когда я рассказываю о прочитанных мною романах Матео Максимоффа, первое, что приходит мне на ум, — это сцена, где Люси попадает в волшебный шкаф и обнаруживает мир, о существовании которого она раньше не подозревала.

На страницах романа «Урситори» нас встречают Pомa — Матео Максимофф всегда писал это слово c заглавной буквы. В цыганском языке ром — это мужчина— цыган родом с Балкан или из одной из стран Восточной Европы. Ром также используется как синоним слова муж. Жена или женщина- цыганка — ромни. Используя эти традиционные цыганские наименования, автор проявляет любовь и уважение к своему народу.

В этой, самой первой книге, мы можем почувствовать близость Матео Максимоффа к историям, обычаям и верованиям цыган. Также он подчеркивает роль женщины в цыганском обществе и заставляют нас задуматься о том, кто они — настоящие ангелы судьбы?

Эта книга родилась из жизненного опыта автора, историй и воспоминаний его родственников, которые он внимательно слушал в детстве и юности, а затем с нетипичной для его возраста бережностью собирал в обширную коллекцию устных рассказов, чтобы впервые изложить их на бумаге, и тем самым открыть перед нами возможность лучше понять мир цыган.

Матео Максимоффу потребовался всего тридцать один день на то, чтобы написать эту книгу, пока он находился в тюрьме по ложному обвинению. Адвокат посоветовал ему использовать в качестве сюжета события, которые привели к его аресту.

Колекція «Матео Максимофф»

Перше французьке видання «Les Ursitory» вийшло одразу після Другої світової війни, під час якої Матео Максимофф пережив жахи концентраційних таборів, як і багато інших представників циганського народу. Саме тому публікація цієї книги, написаної ще наприкінці 1930-х років, відбулася лише через багато років.

Матео був кочовим циганом; у ті часи дуже небагато представників його народу вміли читати та писати. А він умів. І, маючи великий талант оповідача, наважився писати.

Після цього першого роману незабаром з’явилися ще два:

«Le Prix de la liberté» («Ціна свободи»)

«Savina» («Савіна»)

У листопаді 1961 року Матео пережив духовний досвід, який змінив усе його життя. Це відчутно у його пізніших працях. Письменник популяризував циганську культуру і побував у тридцяти трьох країнах, свідчачи про свою зустріч із Богом.

Готуються до видання:

Le Prix de la liberté («Ціна свободи»), 1955

Savina («Савіна»), 1957

La septième fille («Сьома дочка»), 1958

Condamné à survivre («Засуджений до виживання»), 1984

La poupée de Mameliga («Лялька Мамлиґи»), 1986

Vinguerka («Угорка»), 1987

Dites—les avec des pleurs («Кличте їх зі сльозами»), 1990 – продовження Condamné à survivre(«Засуджений до виживання», 1984)

Ce monde qui n´est pas le mien («Світ, що мені не належить»), 1992

Routes sans roulottes («Дороги без кибиток»), 1993